- PMRV

- Background

- Study site

- West Kalimantan

Kapuas Hulu, West Kalimantan

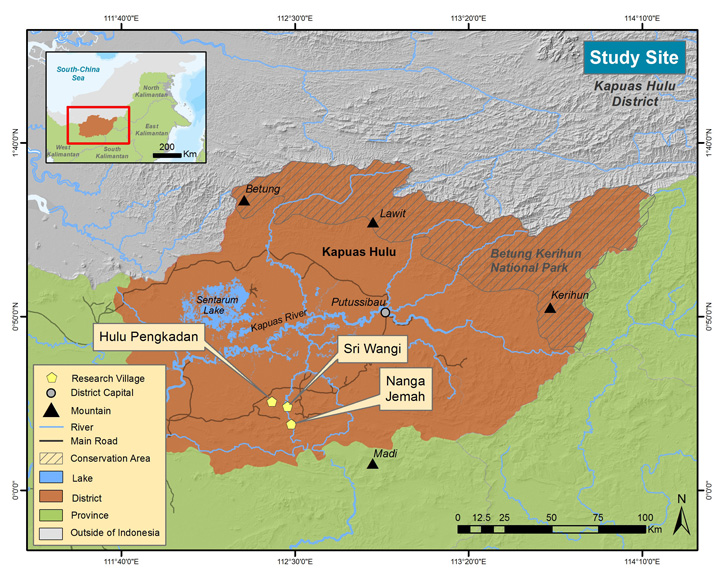

The study is being conducted in the Kapuas Hulu District, the easternmost district in West Kalimantan Province, an area also known as the heart of Borneo Island. Kapuas Hulu is well known for its rich biodiversity and its tropical rainforest that spans a total area of 29,842 km2 (approximately 20% of West Kalimantan’s total area). More than 56% of this forested area is designated as protected, including two well-known national parks: Danau Sentarum (132, 000 ha Ramsar site) and Betung Kerihun (800,000 ha, tentatively on the list of World Heritage Sites). The inhabitants are mainly from two major ethnic groups: the Dayak (with 32 subethnic tribes) and the Malay (also considered a religious identity, it includes Dayak who have converted to Islam). Named after its location in the upper stream (hulu in the local language) of the Kapuas River, the longest river in Indonesia, the area is highly influenced by the river and its many tributaries.

The landscape of the district is relatively flat to the west and mountainous and hilly in the north and south. We worked in three villages situated in the southern part of Kapuas Hulu: one — Hulu Pengkadan — is located near the main provincial road, which extends from east to west, connecting Kapuas Hulu to Pontianak, the provincial capital city; and the other two — Sri Wangi and Nanga Jemah — are positioned far south and are part of the Muller-Schwaner Mountain Range.

Since July 2013 when we began our fieldwork, we have noticed fast and remarkable changes taking place. Two roads have been built, a local electricity grid (listrik desa) has been installed, though some villages are still waiting for connection, and all the villages have undergone population changes with people moving in and out and between the villages. New rubber gardens have been planted, land has been cleared for dry rice (ladang) cultivation, the different seasons have brought seasonal work such as gold mining, iron wood (belian) harvesting and agarwood (gaharu) collecting, and flags and faces of political parties and candidates campaigning for the 2014 legislative election have colored the villages. In two of the villages, Nanga Jemah and Sri Wangi, the Indonesian Minister of Forestry has issued a Village Forest (Hutan Desa) permit, which will solidify village forestland rights while bringing a new local forest management regime.

We experienced the highest flood of the year, persistent monsoonal rains, muddy and adventurous road rides, local celebrations including a baby’s first hair cut, the opening of a new community hall, seasonal diseases such as measles and their cures from local shamans, a variety of seasonal fruits from rambutan and durian to many other tropical fruits that we had never seen or tasted before, and fresh fish straight from the river. We talked and spent time with the villagers, learned from their knowledge and experience of the forest and management practices, observed how they govern their village and the power dynamics around it, and participated in their social and cultural activities.

All the above are pieces of a larger story about how the lives and livelihoods of the people in these three villages are shaped by their historical background and the landscapes around them; a story that we want to learn to understand how an activity such as Participatory MRV could fit into their lives, livelihood needs, and cultural systems.